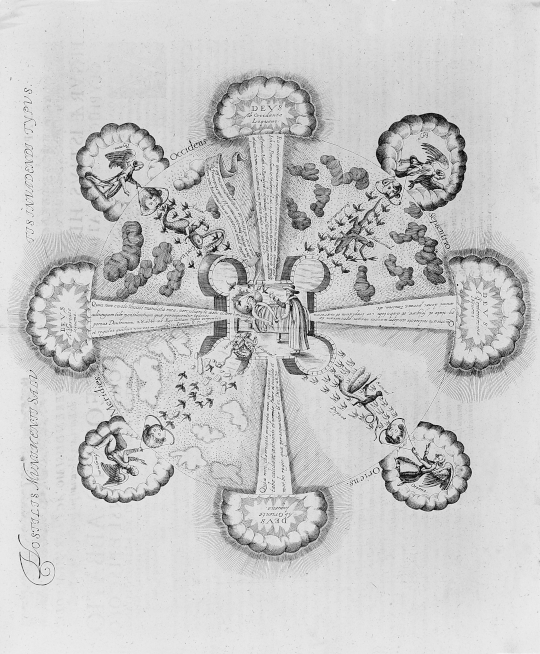

The invasion of the Fortress of Health by Demons depicted as living creatures: Robert Fludd, Integrum morborum mysterium (1631). Wellcome Collection.

Early modern patients and practitioners shared a view of health and disease as a balance between bodily heat and moisture, often expressed in terms of the four humours — blood, bile, melancholy, and phlegm — corresponding to elemental properties of earth, air, fire, and water. Cures entailed expelling the foul humours that caused blockages within the body and restoring the flow of its vital forces. This broad understanding of blockages and flows accommodated divergent understandings between practitioners and their patients of the specific causes of disease, depending on whether they attributed it to, for instance, supernatural or natural forces or poor disposition or emotional upset. Prayer could expel demons just as a purge could expel a surplus of melancholy.

While Forman and Napier insisted that their astrological expertise enabled them to judge the causes of disease better than other practitioners, in practice they and their patients negotiated the meanings of a variety of signs, some observed by the astrologers, others reported to them by their patients and querents. An entry might contain a judgment based on the horoscope, or other sorts of evidence gleaned from the patient’s words or appearance. Patients often brought or sent their urine, even though uroscopy — the use of the colour, consistency and content of urine to signal the state of the bodily humours — an established form of medical diagnosis since the middle ages, was beginning to be discredited. In practice, especially in consultations about whether a woman was pregnant, a question notoriously difficult to discern for certain, Forman and Napier heeded the signs of the urine while questioning its validity. Unlike other physicians, Forman and Napier did not feel the pulse and seem not to have used touch to examine their patients.

Within the medical landscape of early modern England, Forman and Napier were part of a large penumbra of irregular practitioners. Following conventions established within medieval universities and regulated by municipal (which often meant ecclesiastical) authorities, physicians were the medical elite who advised their patients about a healthy regimen, understood the causes of disease, and prescribed fortifying or purgative remedies. Pills, powders, and other remedies were prepared by apothecaries, who were trained and regulated through guilds. Surgeons also operated through guilds, though some of them studied at universities, and were called on to treat ‘external’ ailments such as broken bones, skin lesions, hernias, and kidney stones. Barber-surgeons, as their name suggests, attended to beards and also let blood, as prescribed by a physician. Midwives, regulated by the church, helped to deliver babies, but if problems occurred a surgeon was called, often with a view to extracting the foetus to save the woman. In practice, numerous other practitioners — some with formal training, others not, some quasi-professionally, others very occasionally — offered medical goods and services in early modern England. Licensed physicians typically disparaged those whose knowledge was founded in experience rather than reason and book-learning as ‘empirics’. But the boundaries between regular and irregular practitioners and between formal and practical knowledge were fluid. Through the seventeenth century, the medical establishment faced competing medical philosophies, often aligned with the political and religious factions of that tumultuous century. While practitioners vied for intellectual credibility and paying customers, their patients continued to shop around.

Further reading

- Porter, Roy (1997) The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity from Antiquity to the Present, London: Harper Collins.

- Siraisi, Nancy (1990) Medieval and Early Renaissance Medicine: An Introduction to Knowledge and Practice, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Wear, Andrew (2000) Knowledge and Practice in English Medicine, 1550–1680, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.