by Katherine Foxhall

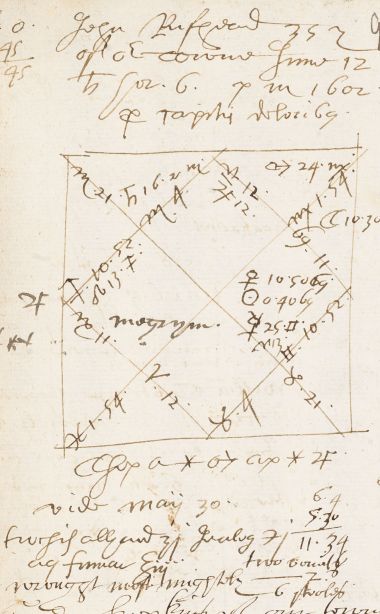

This is one of John Roughead’s entries in the casebooks. MS Ashmole 221, f. 99r. Copyright Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2011.

Goodman John Roughead appears around twenty times in Napier’s cases, once each in Forman’s and James’. Several times Napier described Roughead as a ‘neighbour’ or ‘of our towne’. Proximity partly explains why he so often consulted the astrologer, but it is also clear that Roughead had a longstanding problem with ‘megrim’ (migraine). Roughead first appears to have consulted Napier for his head problems in May 1601 for a ‘hot megrim’ that had been helped by a blow with a flail. In 1602 Roughead visited the astrologer three times; in March he was ‘payned in his head’ (note that the other case on the right hand side of the page also concerns a patient with ‘a megrim and hot rhe[u]me in ye head very paynefull’). In an entry of May 1602 Napier wrote ‘hemicranea’ in the centre of the horary chart; hemicrania was the Galenic term describing a pain in half the head from which the vernacular English word megrim derived. In June, Roughead’s chart clearly again specified megrym as the subject of the consultation. Over the years, Roughead would continue to consult the astrologer for his pain. In January 1607, he would return for a ‘deadly tormenting megrym in his head’, and again in 1609 for ‘great extreeme payne’ in his head. As late as 1619 Roughead was complaining of an ache in his head and hot eyes.

Megrim — like migraine in our own time — was a common disorder in the early modern period. Instructions for the preparation of treatments often appeared in domestic recipe books and printed medical texts, remedies could be purchased from apothecaries, and the waters of places such as Buxton offered another route to potential cure. Among these options, seeking the medical help of an astrologer was, if not common, certainly an accepted addition to these treatments. In addition to Roughead’s queries, Richard Napier’s casebooks contain eighteen cases in which ‘megrim’ was the topic of the question asked of the astrologer. These cases include slightly more men than women, the patients ranging in age from their early twenties to an anonymous ‘old woman’ aged sixty-five. Some of them had long suffered the affliction. Francis Dale (CASE14625) had ‘a megrim & payne in his head of long continuaunce’. Joan Markham (CASE13499) had a ‘contin[u]all megrym’, associated, Napier seemed to suggest, with grief over the death of her son. For some patients, migraine was associated with swelling and sore eyes. Matthew Emerson (CASE19297) was ‘Long sick & payned in the eyes & head eyes blood shotten. long er he was holpen’. Roughead himself eventually found the heat in his head, of which he repeatedly complained, affecting his eyes. The 24 year old Jonas Tanner’s migraines were cyclical and had recurred every three or four weeks for twelve years (CASE22924). When fellow Exeter College student Robert Vilvayne was ‘mutch payned with a megrim’, Napier judged that it was caused by an abundance of phlegm and red choler, and possibly melancholy too (CASE11613); between 1598 and 1601 Vilvayne complained to Napier several times of headaches, along with pain of the stomach and problems with his liver. Roughead, thus, was not alone in consulting Napier for migraine. Napier’s casebooks provide important first-hand evidence — rare from this period — of how the experience of megrim was understood at the turn of the seventeenth century.

Napier may have been consulted about migraine because of its chronic nature, but there is no evidence that his remedies were especially effective. On several occasions Napier prescribed Roughead with ‘jeralog’, his favoured remedy for megrim, a term short for Hiera Logadii, a purgative used against melancholy and to treat vertigo. Rather, Napier acknowledged that Roughead was provided the most ease from the more direct expulsion of corrupt humours. Observing that an accidental wound provided relief, Napier prescribed bloodletting (CASE19344). A later entry recorded that Roughead had had most success with a ‘seton’, a cord or thread passed through a hole in the body. Usually used in the treatment of fistulas, setons were employed against migraines by making the hole for the seton surgically at the back of the neck. The sufferer would wear the seton looped through the skin of the neck for an extended period. Napier remarked that ‘nothing would helpe him but the Seton’, and after this success Roughead disappears from Napier’s practice records for five and a half years — before returning with ague and more head pains.

The consultations

1 November 1598. John Roughead is sick. Napier’s judgment notes problems with his side, his stomach, and his head; the problem is principally with his head, which is ‘extreeme sick & hot’.

3 May 1601. Napier writes that John Roughead ‘of our Towne’ is troubled with a ‘hot megrim’ (as well as a griping in the stomach, pain in his back and a rheum running like water from his nose). He has previously been helped accidentally by being struck with a flail so that he bled. Napier prescribes bloodletting.

2 March 1602. Roughead is still ‘payned in his head’; Napier is now attributing it to the ‘new Disease’ (which he sometimes calls the ‘new ague’). Napier prescribes purgatives (confection of Hamech and an unspecified decoction).

30 May 1602. Goodman (John) Roughead, 39, of Great Linford, has ‘hemicranea’. Again, Napier prescribes purgative medicines (this time confection of Hamech and alhandal).

12 June 1602. Once again Roughead is the patient in a consultation ‘pro capitis doloribus’ (for pains of the head), which Napier specifies as ‘megrym’. Napier refers back to his entry of 30 May, and again prescribes purgatives (alhandal and Hiera Logadii) followed by three ounces of fumitory water (noting the cost ‘2s’ beside these). He later adds that this ‘wrought most mightily’, giving Roughead ‘two vomits’ and ‘6 stooles’.

1 January 1607. Roughead is suffering ‘a deadly tormenting megrym in his hed’. Napier once more prescribes alhandal and Hiera Logadii.

18 January 1609. Gerence James writes that Roughead has a ‘great extreeme payne in his head’. No further details or prescription are recorded.

19 January 1609. Goodman Roughead (aged 45), suffering ‘extreme hed ach’, is prescribed a variety of purgatives; later notes say that it was ‘cured with the seton’ and that ‘nothing would helpe him but the Seton’.

24 January 1609. A consultation for Goodman Roughead once more remarks on his ‘extreeme payne in his hed’. His temples and forehead are sore. No treatment is recorded.

28 July 1614. Roughead has a tertian ague, having had his first fit eleven days ago, shaking for an hour then burning. He looks ill and is very costive, but still has a ‘great hed ach’, and the skin is gone from his mouth from the heat there. Napier prescribes three grains of antimony and six drams of conserve of roses. Later he notes that this ‘wrought well but made him very sicke’.

13 June 1619. Roughead still has a headache; his eyes are red and hot. Napier notes that at some point he was cut on the leg with a hatchet; it took a long time to heal, but that made his head and his eyes well. It is unclear whether the events described here are the same as the injury with the flail mentioned in 1601. The prescription divides his treatment into four stages, including purgative medicines, bloodletting and a water for Roughead’s eyes.

References

- Foxhall, Katherine (2019) Migraine: A History, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.